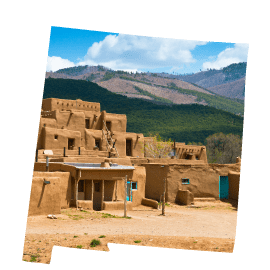

New Teacher Induction: New Mexico

Retaining Effective Teachers Policy

Analysis of New Mexico's policies

New Mexico requires that all of new teachers receive mentoring. The state mandates that all new teachers participate in a mentoring program throughout their first year of employment and that mentors receive additional training. A regular review and evaluation process to assess the program's effectiveness is also mandatory. All other logistics are left to the local districts.

Recommendations for New Mexico

Set more specific parameters.

To ensure that all teachers receive high-quality mentoring, New Mexico should set a timeline in which mentors are assigned to all new teachers throughout the state, soon after the commencing of teaching, to offer support during those first critical weeks of school. Mentors should be required to be trained in a content area or grade level similar to that of the new teacher, and to attract the most qualified participants to the mentor program, guaranteed compensation is also a wise inclusion.

Select high-quality mentors.

While still leaving districts with flexibility, New Mexico should articulate minimum guidelines for the selection of high-quality mentors. It is particularly important that the mentors themselves are effective teachers. Teachers without evidence of effectiveness should not serve as mentors.

Require induction strategies that can be successfully implemented, even in poorly managed schools.

To ensure that the experience is meaningful, New Mexico should make certain that induction includes strategies such as intensive mentoring, seminars appropriate to grade level or subject area, and a reduced teaching load and/or frequent release time to observe other teachers.

State response to our analysis

New Mexico indicated that the state is piloting a new initiative that requires ineffective teachers to be mentored by top quartile teachers as part of a professional growth plan. According to the state, once completed during the 2015-2016 school year, this will be considered to be scaled as a requirement for novice teachers as well as for all struggling teachers.

Select another topic

Delivering Well Prepared Teachers

- Admission into Teacher Preparation

- Elementary Teacher Preparation

- Elementary Teacher Preparation in Reading Instruction

- Elementary Teacher Preparation in Mathematics

- Early Childhood

- Middle School Teacher Preparation

- Secondary Teacher Preparation

- Secondary Teacher Preparation in Science and Social Studies

- Special Education Teacher Preparation

- Special Education Preparation in Reading

- Assessing Professional Knowledge

- Student Teaching

- Teacher Preparation Program Accountability

Expanding the Pool of Teachers

Identifying Effective Teachers

- State Data Systems

- Evaluation of Effectiveness

- Frequency of Evaluations

- Tenure

- Licensure Advancement

- Equitable Distribution

Retaining Effective Teachers

Exiting Ineffective Teachers

Pensions

Research rationale

Too many new teachers

are left to "sink or swim" when they begin teaching.

Most new teachers are overwhelmed and undersupported at the

outset of their teaching careers. Although differences in preparation programs

and routes to the classroom do affect readiness, even teachers from the most

rigorous programs need support once they take on the myriad responsibilities of

their own classroom. A survival-of-the-fittest mentality prevails in many

schools; figuring out how to successfully negotiate unfamiliar curricula,

discipline and management issues and labyrinthine school and district

procedures is considered a rite of passage. However, new teacher frustrations

are not limited to low performers. Many talented new teachers become

disillusioned early by the lack of support they receive, and it may be the most

talented who will more likely explore other career options.

Vague requirements

simply to provide mentoring are insufficient.

Although many states recognize the need to provide mentoring

to new teachers, state policies merely indicating that mentoring should occur

will not ensure that districts provide new teachers with quality mentoring

experiences. While allowing flexibility for districts to develop and implement

programs in line with local priorities and resources, states also should

articulate the minimum requirements for these programs in terms of the

frequency and duration of mentoring and the qualifications of those serving as

mentors.

New teachers in

high-need schools particularly need quality mentoring.

Retaining effective teachers in high-need schools is

especially challenging. States should ensure that districts place special

emphasis on mentoring programs in these schools, particularly when limited

resources may prevent the district from providing mentoring to all new

teachers.

Induction: Supporting Research

Although

many states have induction policies, the overall support for new teachers in

the United States is fragmented due to wide variation in legislation, policy

and type of support available. There are a number of good sources describing

the more systematic induction models used in high-performing countries:

Attracting, Developing and Retaining Effective Teachers – Final Report: Teachers Matter, a 2005 publication by the OECD, examines

(among many other factors) the role that induction plays for developing the

quality of the teaching force in 25 countries. For shorter synopses, consult

Lynn Olson, "Teaching Policy to Improve Student Learning: Lessons from

Abroad," 2007. http://www.edweek.org/media/aspen_viewpoint.pdf

Educational

Testing Service's Preparing Teachers Around the World (2003)

examines reasons why seven countries perform better than the United States on

the TIMSS and includes induction models in its analysis.

Domestically,

evidence of the impact of teacher induction in improving the retention and

performance of first-year teachers is growing. See Impacts of Comprehensive Teacher Induction: Results from the Second Year of a Randomized Controlled Study. National Center for Educational

Evaluation and Regional Assistance. Institute of Education Sciences, Department of Education, NCEE 2009-4072, August 2009.

A

California study found that a good induction program, including mentoring, was

generally more effective in keeping teachers on the job than better pay. See

D. Reed, K. Rueben, and E. Barbour, "Retention of New Teachers in California,"

Public Policy Institute of California, 2006.

Descriptive

qualitative papers provide some information on the nature of mentoring and

other induction activities and may improve understanding of the causal

mechanisms by which induction may lead to improved teacher practices and better

retention. A report from the Alliance for Excellent Education presents four

case studies on induction models that it found to be effective. See Tapping the Potential: Retaining and Developing

High-Quality New Teachers, Alliance for Excellent Education at: http://all4ed.org/wp-content/uploads/2007/07/TappingThePotential.pdf.

For evidence of the importance of high

quality mentors, see C. Carver and S. Feiman-Nemser, "Using Policy to Improve Teacher Induction: Critical Elements and Missing Pieces." Educational

Policy, Volume 23, No. 2, March 2009, pp. 295-328 as well as K. Jackson and E. Bruegmann in "Teaching Students and Teaching Each Other: The Importance of Peer Learning for Teachers." American

Economic Journal: Applied Economics, Volume 1, No. 4, October 2009, pp. 85-108. See also H. Wong, "Induction Programs that Keep New Teachers Teaching and Improving," NASSP Bulletin, Volume 88, No. 638, March 2004, pp. 44-58.

For

a further review of the research on new teacher induction see M. Rogers, A. Lopez, A. Lash, M. Schaffner, P. Shields, and M. Wagner,

"Review of Research on the Impact of Beginning Teacher Induction on Teacher Quality and Retention," ED Contract ED-01-CO-0059/0004, SRI Project P14173, SRI International,

2004.

The

issue of high turnover in teachers' early years particularly plagues schools

that serve poor children and children of color. Much of the focus of concern

about this issue has been on urban schools, but rural schools that serve poor

communities also suffer from high turnover of new teachers.

Research

on the uneven distribution of teachers (in terms of teacher quality) suggests

that, indeed, a good portion of the so-called "achievement gap" may

be attributable to what might be thought of as a "teaching gap,"

reported by many including L. Feng and T. Sass, "Teacher Quality and Teacher Mobility," Calder Institute, Working Paper 57, January 2011; T. Sass, J. Hannaway, Z. Xu,

D. Figlio, and L. Feng, "Value Added of Teachers in High-Poverty Schools and

Lower-Poverty Schools," Calder Institute, Working Paper 52,

November 2010; and C. Clotfelter, H. Ladd, and J. Vigdor, "Who Teaches Whom? Race and Distribution of Novice Teachers," Economics of Education Review, Volume 24, 2005, pp. 377-392.

See

also B. White, J. Presley, and K. DeAngelis, "Leveling Up: Narrowing the Teacher Academic Capital Gap in Illinois," Illinois Education Research Council, Policy Research Report: IERC 2008-1, 44 p.