Teachers are not interchangeable parts in a school district. That's why principals need to have the final say about the district's decision to transfer a teacher into their school. Principals and other school leaders are best positioned to know if a certain teacher will be a good fit for their school and their community, and they have a significant interest in making sure that any teacher who comes into their building is successful. In this District Trendline, we examine how decisions about teacher transfers are made in the largest school districts across the country.

What happens when a teacher chooses to be transferred?

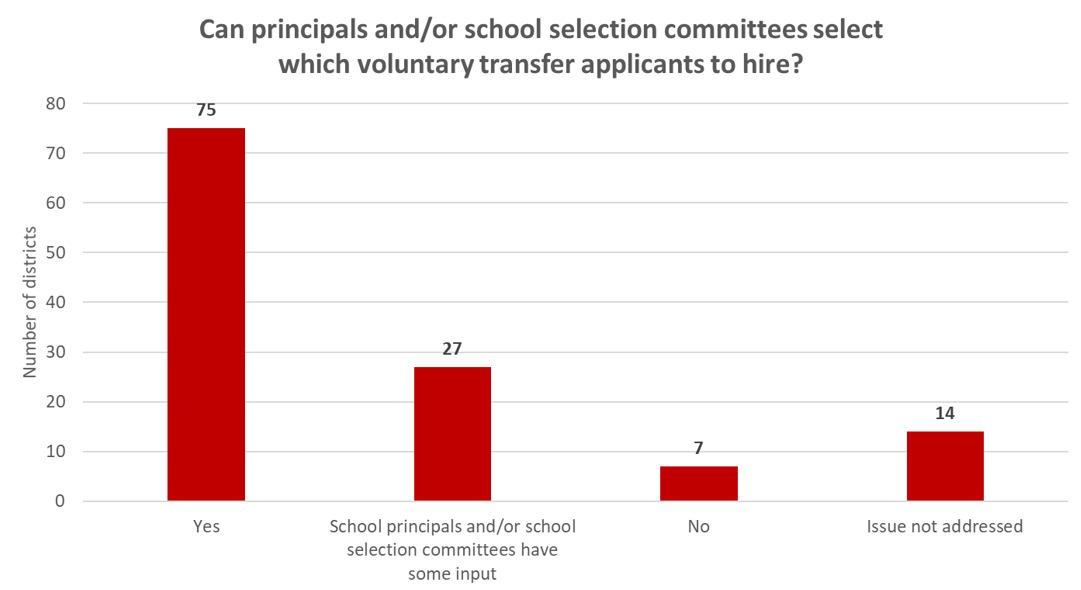

Most teacher transfers within a district happen when a teacher requests to change schools. For these voluntary teacher transfers, most of the 123 large school districts in our sample give their principals a say in the transfer decision.

In the 75 large districts that put principals in charge of selecting which voluntary transfer applicants to hire, four districts— Clayton County Public Schools (GA), DeKalb County School District (GA), Desoto County School District (MS), and School District of Lee County (FL)—give the central office final approval authority over the decision. Three additional districts—Anne Arundel County Public Schools (MD), Clark County School District (NV), and San Diego Unified School District—give their school principals (or selection committees) a say until a certain point in the school year. Voluntary transfers that happen after the deadline in those three districts are forced placed by the central office.

For the 27 large districts that give principals or school selection committees some input, it typically means one of two things. First, it might really mean that the district's central office is the final arbiter, but they are required to consult with school principals or committees. Second, it might mean that the central office assigns transfers to a particular school, but principals or committees have ultimate approval authority.

Only seven of the largest districts still explicitly place voluntary transfers in schools without a requirement that they even consult with school leaders: Cumberland County Schools (NC), Long Beach Unified School District (CA), Manchester School District (NH), Milwaukee Public Schools, Oklahoma City Public Schools, Portland Public Schools (ME), and Santa Ana Unified School District (CA).

What happens in cases of involuntary transfers?

In the case of involuntary transfers, school principal or selection committee input is much less common; only 20 of the largest districts have mutual consent policies that ensure both the teacher and principal agree on a placement.

Involuntary transfers, sometimes called excessing, usually happen when there is a change in student enrollment, school budget, or school programming, reducing the need for the number of teachers in a particular building. While 47 of the largest districts do not address the process for placing involuntary transfers (which may mean that principals do not have the authority to reject a transfer), more than 60 percent of districts with a stated policy give the central office full authority.

In nine of the large districts, while the central office does place involuntary transfers, the school leaders have some input. In Brevard Public Schools (FL), for example, the principal may refuse any involuntary transfer candidate whose rating was less than effective.

Sometimes with involuntary transfers, ineffective teachers are moved out of a school only to be forced placed in another school in the district by the central office. This "dance of the lemons," as it has been called, can be ended by the adoption of mutual consent policies—but such policies are not without new challenges

Mutual consent: the way forward

A mutual consent policy relies on the consent of both teacher and principal for a transfer decision, rather than having the central office decide the transfer. In order to hold principals accountable for the outcomes of their school, some degree of freedom in how they constitute their faculty appears appropriate. Surveys also show support for mutual consent among teachers, and have found higher levels of job satisfaction reported by teachers who were given more say in their placement.

Mutual consent policies are not without their challenges. If a school district no longer force places teachers, there will be teachers that cannot find a position. This circumstance can lead to districts spending money on teachers who are not in the classroom, or the new challenge of how to deal with dismissal of these teachers. For more districts to adopt mutual consent will require change at both the state and local levels.

Ongoing efforts have been successful in overcoming some of these challenges of mutual consent. A state law in Colorado allows teachers to be put on unpaid leave if they cannot find a placement through mutual consent, though not all districts take advantage of the option. However, Colorado is the only state in the nation with such an explicit policy. Oddly, the state legislature in Illinois allows Chicago Public Schools to put unplaced teachers on unpaid leave, but Chicago is the only district in the state with permission to do so. Other districts with mutual consent policies require unplaced teachers to work as substitute teachers, also a costly decision by a district, as a salaried teacher earns so much more than a substitute teacher. In Oakland Unified School District, involuntarily transferred teachers who can't find a teaching position are offered instructional support roles.

Still, the popularity of mutual consent policies continues to grow. Over this past summer, the school board of Los Angeles Unified School District announced the intention to essentially create a mutual consent policy for the lowest performing 50 schools in the district.

To further explore this and dozens of other teacher policies in the largest school districts across the country, check out the Teacher Contract Database.

To get the NCTQ District Trendline delivered to your inbox each month, subscribe here.