In this unprecedented time of school closures, districts must walk a fine line regarding teacher evaluations. Districts must hold teachers harmless from the challenges unique to the coronavirus environment, but they also have a public obligation to make sure students are being taught as effectively as is practical to expect. It is a new world. Currently, it is as if every teacher is a first-year teacher again, and they need extra support. Meanwhile, many students will fall behind in these months, starting the 2020-2021 school year at a disadvantage.

Now more than ever, teacher evaluations, albeit retooled, could provide the support teachers require and the oversight students need. Providing feedback and support to teachers can both equip them presently as they adjust their practice to distance learning, as well as guide focus areas for future growth once students and teachers return to their physical classrooms.

While we have a good sense of how states are responding on teacher evaluation policy, so far there's been less focus on what districts are doing, which is where the rubber actually meets the road. In the last few weeks, some districts have begun to define their evaluation policies to fit the current times, although it appears that most of the large school districts NCTQ tracks have yet to do so. We hope that our review and analysis of this first set of districts will serve as guidance to other districts as they undertake this important work.

What are districts doing in the area of teacher evaluation?

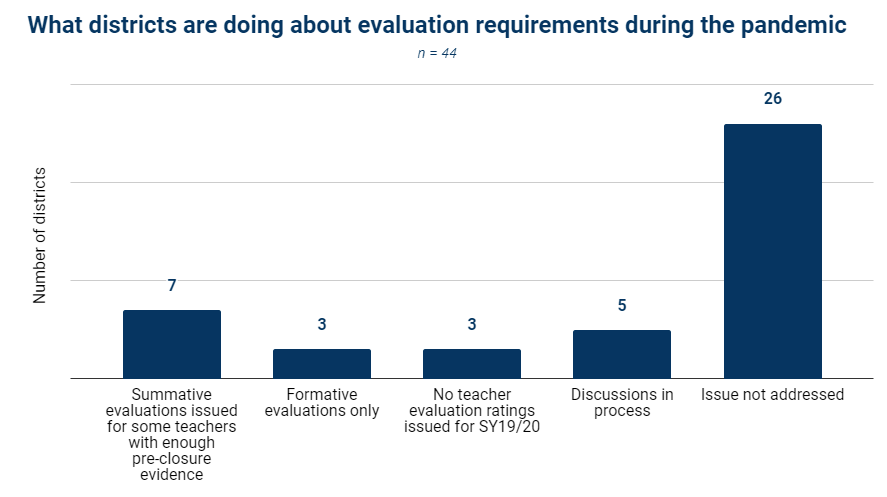

Since our initial analysis of district policies in early April, more districts are now coming to formal agreements with their teachers unions to address this new coronavirus reality, and these agreements are starting to include evaluation procedures. Of the 44 districts we have examined so far for specific language pertaining to teacher evaluations, only 18 mention teacher evaluation in the context of school closures and distance learning, and only 13 of those 18 have made a concrete decision about it. The remaining five—Baltimore City, Broward (FL), Denver, Miami-Dade, and Minneapolis—are in the middle of discussions with either their boards or unions, and we expect that the result of those discussions will include guidance regarding teacher evaluations.

See all district data and citations.

In our analysis of the 13 districts that have made any kind of concrete decision regarding evaluations, we have found three general types of responses: 1) suspend the evaluation process, 2) keep only formative evaluations, or 3) issue summative evaluations when possible.

Hillsborough County (FL), Pinellas County (FL), and Shelby County (TN) have stopped the teacher evaluation process for the rest of the 2019-2020 school year. Hillsborough, in particular, is instead using last year's evaluation ratings for contractual purposes. For teachers that do not have a 2018-2019 rating, the district will either use the most recent rating on record, or issue an "Effective" rating. Teachers who received a rating less than "Effective" in 2018-2019 can apply to the Evaluation Review Committee and request to be deemed "Effective."

Three districts have indicated that evaluations will only be formative this year. In New Mexico, Albuquerque is encouraging schools to use data already collected to support teachers and provide feedback to them, but they will not issue evaluation ratings for the current school year. Similarly, in Massachusetts, Boston is keeping in place observation and feedback through available means, suggesting teachers may be observed remotely, but not providing summative ratings. Dallas ISD in Texas has waived evaluation and observation requirements for 2019-20, though "campus leaders are encouraged to provide informal feedback that will facilitate teacher growth." Dallas will be using 2018-19 teacher evaluation data to determine the base salaries of returning teachers.

The most common policy we have seen so far, adopted by seven districts—Chicago, Hawaii, Long Beach (CA), Los Angeles, San Diego, San Francisco, and Seattle—is issuing summative evaluations for all classroom teachers for whom enough evidence was collected before the closure, while cancelling or delaying summative evaluation ratings for teachers without enough evidence before the closure started. Seattle is only issuing formal evaluation ratings for teachers if they score "Proficient" or higher, but included a specific provision for supporting teachers on improvement plans. Hawaii is allowing the completion of evaluations and rating of teachers where possible, but holding teachers harmless where not. Finding this balance is particularly important given the difficulties in accountability and the steep learning curve in this new environment.

With many students presumed to start the 2020-2021 school year behind, districts should make sure teachers continue to receive feedback and support. We commend some of the aforementioned districts in this last group that are focused not only on providing summative feedback but also on ensuring teachers get timely support. For example, San Francisco is allowing for continued observations during distance learning, but these new observations will not impact any evaluation ratings.

Final considerations

It is clear that some measure of evaluation of teachers' performance is required, not only to make sure that teachers are being as effective as possible in teaching the country's students, but also in order to provide support during this time of upheaval. The learning process that teachers face is very steep in this era of remote instruction; it is all new, and there are no tried and true methods anymore. The many new issues cropping up are challenges teachers have never had to deal with before.

Under these circumstances, it is critical that districts continue providing teachers with the feedback and support they need to continually improve. In the immediate term, districts should consider ways to continue giving teachers formative feedback during remote learning, like in Boston and San Francisco, as well as offering professional development to teachers based on needs identified through observations and teacher input. This will also help principals be able to assess how their teachers are coping with their new workloads, including how they are delivering instruction, giving assignments, and providing feedback to students.

In the longer term, districts should not lose sight of the need to support teachers in their eventual return to the physical classroom. They should ensure teachers receive all of the feedback collected prior to school closures, as Albuquerque is doing, whether or not they issue summative evaluations.

See the District Policies on Emergency School Closures NCTQ tracking sheet for the most updated information and citations.

Updated May 4, 2020 to reflect that Dallas ISD's school board waived the teacher evaluation requirements for 2019-20.