As school districts work out next year's instructional format and take stock of their teacher workforce, districts in a position to hire are also readying themselves for a potentially unprepared influx of novice teachers. School administrators have the difficult task of ensuring that new teachers are effective regardless of setting, while also having to bridge the learning loss exacerbated by last spring's dramatic turn of school.

On top of this, administrators will want to minimize the cost of turnover that an unprepared and overwhelmed teacher workforce could impose on the district. A recent analysis of the last four decades of teacher attrition and retention studies shows substantive scholarly agreement on higher attrition of younger and less experienced teachers.

One policy solution is for school administrators to focus their support on less experienced teachers who are more likely to leave. The positive impact on teacher retention associated with strong teacher support systems—particularly new teacher induction via teacher collaboration, professional development, and mentoring—is well-documented. In this District Trendline, we examine those policies for 124 large school districts across the country: the 100 largest districts plus the largest district in each state.

How do districts currently support their novice teachers?

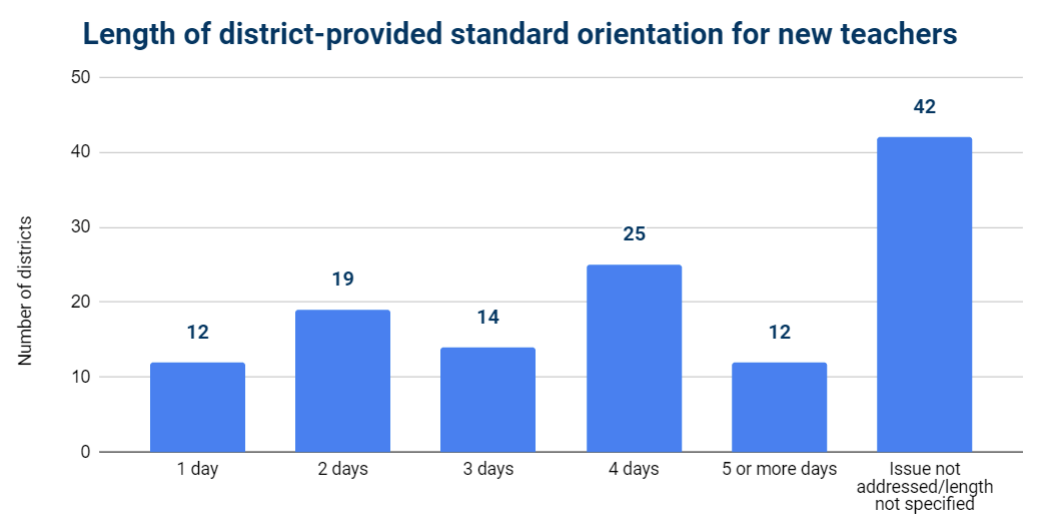

According to the latest board policies or bargaining agreements, 82 districts in our sample address the length of the district-provided orientation, ranging from 3-4 hours in Desoto County School District (MS) to 6 days in Mesa Public Schools (AZ).

When it comes to mentoring new teachers, 92 of the districts in our sample specify the length of their mentoring programs. Some last as little as 30 weeks, such as in Newark (NJ), or up to 4 years, as is the case for all of Ohio's teachers through their Resident Educator Program. Thirty-five percent of districts offer mentoring programs lasting up to one year.

A joint study by Mathematica and the Institute of Education Sciences conducted an experiment to evaluate the impact of mentoring, finding positive effects on student learning only after 2 years of full-time mentoring. By that standard, over half of the districts in our sample may not be equipping their novice teachers in a way that would make a difference in their effectiveness.

As is, we can surmise that many districts under normal circumstances likely do not have an adequate amount of mentoring. This year, however, the need is even greater as many novice teachers will arrive with less preparation than usual, with some still working to complete their certification requirements during their first year of teaching.

Professional development and collaboration

It will be a challenging year for more experienced teachers as well, even more depending on their school's instructional modality, and they will also require extra measures of support to improve or modify their skills to match the current needs of the education industry.

While some districts waived professional development requirements once schools suspended in-person instruction last spring, it is encouraging to see that other districts remained committed to providing such support. Bismarck Public Schools (ND) illustrated this commitment, as they continued to offer remote professional development to their teachers, with an emphasis on how to deliver distance learning.

If instruction is to continue to be delivered remotely in the fall, districts can take a cue from Bismarck's distance learning plan, which includes instructional coaches who delineate learning targets for remote instruction and "work with teacher leaders to develop capacity in planning and delivering quality distance learning."

As districts switched to remote instruction, it became immediately clear that their teachers would be more successful if they didn't have to go at it alone. Teachers shared resources to help each other during remote learning, and the more effective ones made collaboration a constant practice.

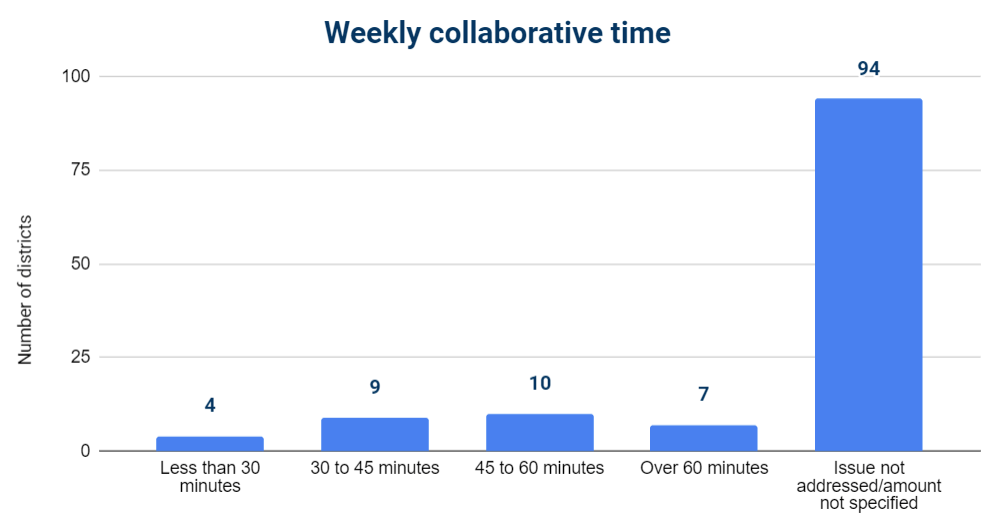

Currently, only a quarter of the districts in our sample explicitly incorporate collaborative time into the teacher's weekly planning time. Of those that do make specific provisions for teacher collaboration, about half allocate 45 minutes or less per week for such.

Strategies for a better chance to succeed

If teachers are to succeed in whichever instructional format they have to face during this upcoming year, they should not do it alone.

Here are some ways in which district policymakers and school administrators can create support structures for their teachers before the next school year begins:

- Increase orientation time for new teachers to adequately help them set expectations and navigate the school's culture and instructional setting.

- Structure mentoring programs for novice teachers to provide support and address their particular needs for at least two years.

- Explicitly prioritize collaborative time into all teachers' planning time.

- Commit to professional development, especially if teachers are expected to continue with remote instruction.