Districts' policies should enable teachers and administrators to fully capitalize on the benefits provided by strong evaluation practices. Looking at 123 districts in NCTQ's Teacher Contract Database, we assess how they measure up on common metrics of a strong teacher evaluation policy:

- That all teachers are evaluated every year,

- that there are multiple observations per evaluation cycle,

- that teachers receive written feedback and have a conversation after each observation,

- and that districts use multiple measures or components to make up a teacher's evaluation rating.

Are all teachers regularly evaluated?

A study out last month found that in Los Angeles Unified School District's lowest-performing schools, more than two-thirds of teachers are not regularly evaluated. Unfortunately, this is not out of the ordinary.

Our data show that 52 percent of the largest school districts do not require that all teachers be evaluated every year. While districts appreciate the need for frequent evaluation of new teachers (all 123 of the largest districts evaluate inexperienced or non-tenured teachers at least once a year), districts do not see that need for more experienced teachers.

In over half of the districts, tenured teachers can go two to five years between full formal evaluations, as long as their previous evaluation rating was proficient or above. In the interim, many districts evaluate these experienced teachers using abbreviated evaluations, such as only using student growth data or bypassing some of the metrics.

How often and for how long are teachers observed?

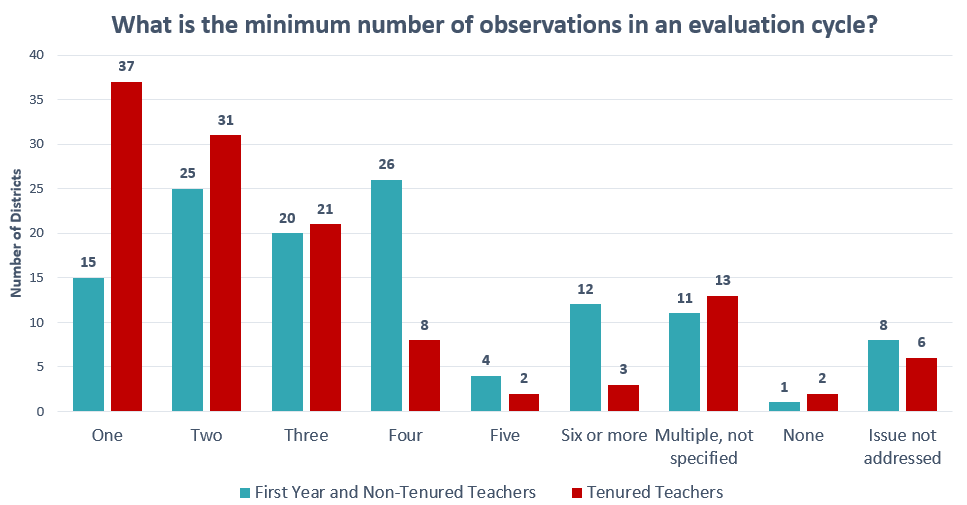

A fundamental part of teacher evaluation is classroom observation. The graph below shows the minimum number of observations districts require in each evaluation cycle for both inexperienced and tenured teachers in the 123 largest school districts. An evaluation cycle in these districts can range from one semester to five years.

For inexperienced teachers, who are all evaluated at least annually in these districts, the majority receive multiple observations throughout the school year. However, 55 percent of districts only require one or two observations per evaluation cycle for tenured or experienced teachers.

These need not all be formal (e.g., covering most of a lesson and including a feedback conference). Three districts are noteworthy for their practices; Gwinnett County Public Schools (GA), Indianapolis Public Schools (IN), and Wichita Public Schools (KS) require at least six observations per evaluation cycle for tenured teachers. They require at least two formal, but then four to seven informal (often shorter) observations or walkthroughs, ensuring that observers are getting multiple and frequent exposure to each teacher's classroom.

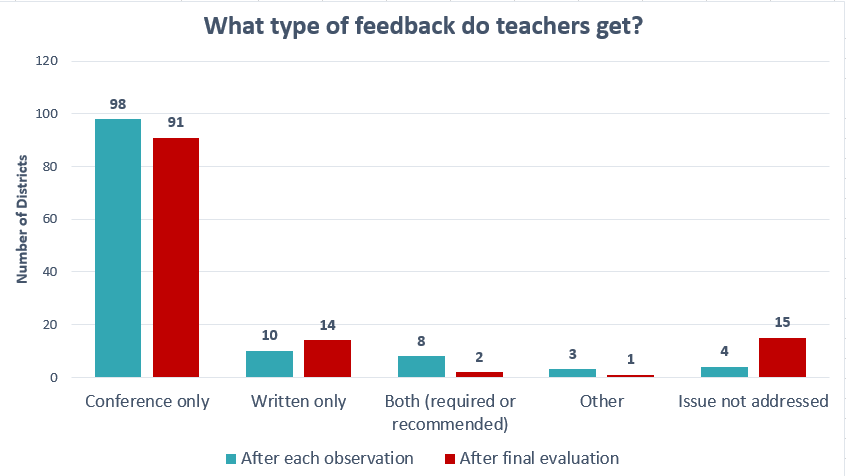

What type of feedback are teachers getting?

Teachers should be provided feedback promptly after each observation in the form of both a conversation with the observer and a written summary. Both a conference and written feedback are also important following teachers' final evaluations. The formative value of observations and evaluations depends on teachers having the opportunity to reflect with their observers and evaluators.

Some noteworthy districts: Atlanta Public Schools (GA) and Chicago Public Schools (IL) require observers to provide written comments and have a conversation after each observation, while Austin Independent School District (TX) and Jordan School District (UT) require both after each final evaluation.

On what are teachers evaluated?

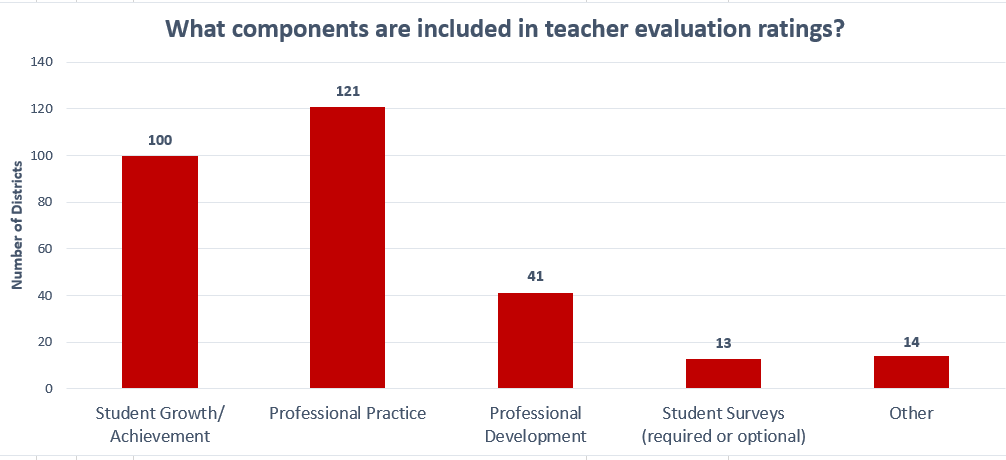

A teacher's job is multifaceted, and so teachers should be evaluated using multiple measures that capture different elements of their practice. Moreover, evaluation ratings are more stable and better at identifying more effective teachers when they combine three general measures: professional practice, student growth, and student survey data. One-third of districts also include a professional development measure to capture how teachers are continuing to learn and grow in their practice.

Twelve districts (mostly in California) only evaluate teachers on one measure: professional practice, which is based on a teacher's classroom observations.

Another 58 districts only include two measures in a teacher's evaluation (most commonly professional practice and student growth). In districts with multiple measures, the professional practice component typically makes up the plurality of a teacher's evaluation rating.

The types of components included as measures in teacher evaluations in these 123 largest districts are shown in the graph below.

Some noteworthy districts: teacher evaluations in Alpine School District (UT), Clark County School District (NV), Mobile County Public Schools (AL), and Shelby County Schools (TN) include all four measures charted here: student growth, professional practice, professional development, and student surveys—a complex (though never complete!) picture of a teacher's performance.

For more on this issue, see: